How COPE Can Help You

Those of us living with the loss of a loved one are often left to deal with our pain alone.

Having experienced profound loss ourselves, COPE families understand the pain, frustration, and isolation those in mourning often experience.

COPE connects individuals who have experienced similar losses by offering ongoing emotional support, sensitive and therapeutic programs, and appropriate resources and referrals. By providing help and support, we enable grieving individuals to find strength from within to face the difficult journey that lies ahead.

Upcoming Events

Connect With COPE

Recent News

Healing Tip – April 2024

The month of April holds National Siblings’ Day on April 10. This day is set to celebrate and...

Healing Tip – March 2024

March is Social Worker Appreciation Month and has Creative Arts Therapy Appreciation Week! And...

Co-Presidents’ Message – February 2024

I had a hard time figuring out what I wanted to share with all of you this month. The more I...

In Memory

COPE Memorial Labyrinth

With dedicated bricks supporting COPE and the grieving community

Memory Wall

Add a message for your loved one.

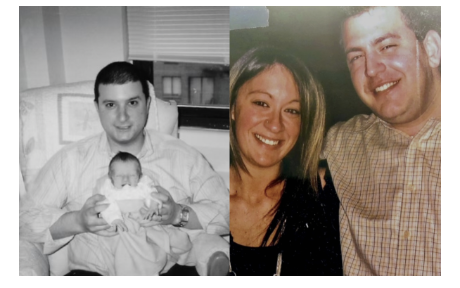

Honoring Our Loved Ones

Share a picture of your loved one